More men than women are affected by ear buzz, but the consequences are greater for women. Women also have a higher risk of severe

hereditary tinnitus, according to a research project.

He is the leader of the TIGER project, in which several European researchers are collaborating. One of their objectives is to investigate gender differences in tinnitus.

“For instance, there were many indications that severe tinnitus increased the risk of suicide attempts among women, but not among men. This is what incited the TIGER project, which further motivated us to explore the sex and gender dimension of tinnitus,” he says.

A passing thing for most people

Jan Bulla is a professor at the Department of

Mathematics, University of Bergen, and part of the same project. He explains that tinnitus is a non-existent sound, but something one experiences as a tone or a buzz in the ears.

“Sometimes people experience tinnitus after having been to a concert or a night club. This is normally a passing thing.”

There are few explanations to what causes tinnitus, apart from such things as hearing impairment, head injuries or jaw-related pain.

“According to physicians people experience tinnitus for many different reasons. This may also help explain why such a large part of the population, up to twenty per cent, experience it”, Bulla says.

For most people then, tinnitus is a passing thing, but for some it becomes permanent.

“It can be extremely uncomfortable and it affects the quality of life”, Bulla says.

Approximately one per cent of the population are affected to such an extent that it becomes debilitating according to the researcher.

No effective treatment

“There are no effective treatments other than cognitive behavioural therapy. We therefore need more research on what causes tinnitus and how it may be treated,” he says.

Cederroth emphasises that since there is no one-size-fits-all treatment, we are far from finding an effective treatment.

“Recent research results indicated that men and women respond differently to the existing treatment methods for tinnitus,” says Cederroth.

“But it will take time before these differences will be taken into consideration in medical practice,” he believes.

Gender differences in heridity

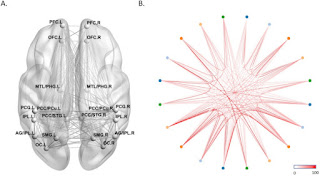

Bulla explains that tinnitus is often found in connection to afflictions such as headache, pains in the jaw and sound hypersensitivity. Early in the project, the researchers studied whether gender was a significant factor for tinnitus in connection to other afflictions.

“We expected to find gender differences here, but we found nothing except for the fact that women with tinnitus more often experience pains in the jaw,” he says.

Another trend that the researchers observed indicates that the connection between headaches and tinnitus is more prominent among men. But according to Bulla, they need to study a bigger data selection in order to know for certain.

“But we did find that women have a higher risk of severe hereditary tinnitus than men have.”

In one study, the researchers counted how many family members of a participant with tinnitus who experienced the same type of tinnitus.

“The gender differences are particularly clear in cases of constant and severe tinnitus. In other words, genes can play a significant part in this type of tinnitus”, Bulla says.

Difficult to research

The gender aspect of tinnitus has not been sufficiently studied before, but more research has been done on the topic in recent years, according to the researchers behind the project.

“I think the reason why gender differences have not been explored much in research on tinnitus is that the researchers often have very limited data material with small sample sizes to work with,” says Bulla.

According to him, gender differences in medical research have often been ignored due to the risk of losing statistical significance when data selections are divided into smaller groups based on gender. The data are often also divided into the participants’ type of tinnitus.

“The situation becomes even more complicated when examining severe tinnitus, since this phenomenon is not that common in the general population,” he says.

Moreover, Bulla emphasizes that their data material on tinnitus comes from few geographical areas.

“Much of the data we have are from Sweden. So we cannot know for certain whether the results apply to other countries or continents.”

May come from hearing loss

Bo Lars Engdahl is a researcher at the Norwegian Institute of Public Health. He studies hearing and has contributed to the health study HUNT, which measures hearing and tinnitus among other things.

“In this study, we found that the prevalence of tinnitus was slightly higher among men,” says Engdahl.

This is related to the fact that men are more often hard of hearing. In Norway and the western world in particular, this is probably because women are less exposed to noise than men are, according to Engdahl.

“Hearing loss increases the risk of tinnitus, and tinnitus often occurs in the same area of the ear as the hearing loss. Your brain compensates for the loss of hearing.”

“It's like a phantom pain in the auditory system”, he says.

Men more often in noisy professions

Engdahl has also studied gender differences in tinnitus within various occupations. He found that bad hearing and tinnitus are more common within noisy occupations.

“Men are in the majority in these occupations,” he maintains.

More men than women are construction workers, mechanics and mine workers. But among the women, tinnitus was not most frequent among those working in noisy occupations.

“The professions in which loss of hearing was most common among women were positions such as laboratory assistants and office workers. In other words, not particularly noisy occupations.”

The majority of the women suffering from tinnitus fell under the category ‘no reported occupation’, which consists of homemakers and unemployed among others. This group was larger among the women, and there were also more women suffering from tinnitus in this group, Engdahl says.

“In the study, we did not only ask whether they experienced ear buzz, but whether they were troubled by it. Other health effects and stress related to unemployment, for instance, could cause increased affliction.”

Tinnitus more bothersome than hearing loss

The research project in which Engdahl has participated demonstrates, like the TIGER project, that many people are bothered by ear buzz. In the Hunt 2 survey in the late 1990s, researchers found that approximately 15 per cent of the population reported that they were bothered by tinnitus.

“A few people, however, suffer from such major affliction that the tinnitus takes over their lives. And to many, the tinnitus is more bothersome than the hearing loss.”

Engdahl also emphasises cognitive treatment as one of the few methods to treat tinnitus; in other words, there is no medicine you can take to get rid of the affliction.

“This treatment revolves around rendering the tinnitus harmless and gradually becoming friends with, or forgetting, the ear buzz. However, not everyone is receptive to this treatment.”

Since there is a clear link between hearing loss and tinnitus among some of the affected, hearing aids may also be helpful.

“Then you will hear several, competing sounds,” Engdahl explains.

“When it comes to tinnitus, the only thing that helps is to forget that it's there. But it's also an advantage if you're able to avoid things that might cause hearing loss. One of the treatments is also to endure more and more sounds – a type of sound therapy”, he says.

Warns against sound anxiety

Engdahl also warns against becoming afraid of sounds. You should look after your sense of hearing and be careful not to expose yourself to extremely loud sounds such as firecrackers and gunshots without using ear protection.

“But you should not be afraid to use your hearing. Normal sounds are not dangerous, and the ear is created to hear relatively loud sounds, also in nature.”

“Neither should you be worried about getting tinnitus from listening to music or being out among other people”, he says

Engdahl emphasises that if you get ear buzz after a concert, for instance, this is an indication that your sense of hearing has been overexerted, but the buzzing will disappear as soon as your sense of hearing has been restored. However, ear buzz is an important warning signal telling you that your sense of hearing is being overexerted, he maintains.

According to the researcher, the sense of hearing among the population seems to be going in the right direction, which is a positive sign.

“Those who were in their sixties and seventies twenty years ago were more hard of hearing than the same age group today. So we are heading in the right direction,” says Engdahl.

“I hope the same applies for tinnitus in the future, although studies indicate that the prevalence of long-term ear buzz is approximately the same today as twenty years ago.”